How to be fired gracefully

You should however seek solace in the fact that we won’t offer up advice here on how “not to get fired” because none exists. This is because 9 times out of 10 it will be out of your hands (see Test Screenings in Part 2), and will often have little or nothing to do with anything you have done or indeed have failed to do. If you messed up, failed to deliver demos on time, stopped answering phone calls, then you can probably remedy how best to avoid this situation in the future. Other than that welcome to the club...

The thing to do is to go quietly and wish them all the best with the movie. If you’re honourable in defeat you may find that good comes out of this situation, a sound man may put you up for a job saying “I thought what you did on X was brilliant and thought the way you were treated was awful”. One thing universal to composers being fired off jobs last minute is it’s usually a sign that the film is in trouble, and is testing badly (see Test Screenings in Chapter Two). The footage is in the can, the edit has gone on for 14 months, the actors are refusing to do any more ADR, the narration track has gone on and off, has been re-written and is back on again, read by the director. Now all they can do, the last piece of the creative puzzle is the score. So the score has to fix the whole shebang. In come the execs, “who is this Charley who’s doing the score, we need THE FIXER, call Hans we’ve got three days left to save this picture!!!”.

If I had a single piece of advice, it would be to book yourself on the first plane out of town and go and lie on a beach somewhere nice. Safe in the knowledge that if you were still in gainful employment you’d be wrestling cues onto a turkey of a show with little to no time to prepare for your sessions, shaving years off your life like they were strips of Doner Kebab with every “overnighter” cigarette and can of Red Bull. All being done whilst an exec peers on with distrust clutching a well thumbed business card with John Powell’s email address on it

So slap on the factor 30 and enjoy!

If however you have made it to the home straight this is where no matter how organised you’ve been, how successful your relationship has been with your director, how smooth a process it has turned out to be. You’re going to get a bit knackered before you get over the finish line. The biggest killer throughout production is the fear of the unknown, and for the inexperienced this will be literally everything. The first unknown will be “how long will x take”. Well in truth it will take as long as you give it. But, if you take it from a veteran, understand that the single biggest threat to your production is you being sleep deprived. So, unless you only have 24 hours left and have loads to do, MAKE SURE YOU GET SOME SLEEP. Your position should be, “OK, I now have only 6 hours possible sleep and if I don’t take it I’m putting the production at risk, so unfortunately for the Director I’m not going to be able to deliver v34 of 1m13 tonight as promised”. Easier said than done. But watch, the biggest mistakes that will happen, the ones that will have you taxi-ing across town to grab a missing bit of data whilst an orchestra waits (done that) will occur because you didn’t get enough sleep, and you therefore shouldn’t be operating heavy orchestral machinery.

But you’re not there yet, let’s first get signed off.

Getting your cues over the finish line

As production looms this is the point that the four inner jobs will start competing for oxygen and will all work against each other. The composer will feel that the main love theme is a bit shit, the DAW ninja will think the love cue could be better off without that clumsy 11/8 bar in the middle after the last recut, the HOD will be looking at the calendar thinking “if we don’t get this fucking love cue to the orchestrater we’re gonna be fucked”, the inner producer is fiddling with hi-hat sounds, whilst the salesperson isn’t even mildly convinced this cue is worth talking up. You’re basically five dogs chasing five tails.

The first thing you need to do is assert yourself as a HOD and do some sums and let everyone know (including yourself) when the score needs to be locked. This means, “I stop taking notes on THIS day”. Your orchestrator and copyist will need AT LEAST a day for every 10 minutes of music you deliver, you will need two hours to track-lay each ten minutes and an entire day to review your track-lay against the scores. This can all happen in conjunction with each other, and indeed you can still be composing whilst “feeding” your orchestrator and copyist. So with that in mind this is when you need to pull the director into the trench with you as opposed to suffer in silence, or indeed go whirling your stroppy composer cape all over the post production department saying “no, finished, too late, fuck you!”. The best way to pull the director and producer in is to confide that whilst the score should be locked, provided you can get 60% of the cues signed of by X then you’ll have ’til Y to really try and figure out that love theme.

Final cut

It is highly likely that you will already have cues signed off and ready to go the minute the final cut hits your department. If you’ve been using Pro Tools like we suggested line up the new picture with your existing demos and quickly skim through the entire picture making notes. These should range from “shift down by 10 frames and speed up by a couple of BPM” to “complete car crash don’t know what they’ve fucking done here”. That way you’ll be able to attack cues in order of how quickly you can get them out of the door.

So what’s the quickest way to do this with a new picture? We’d recommend first that you snip the front of all the cues at the time code of bar 1 (or record them that way in the first place). Then put the new picture and its sound tracks at the top of your session, and group together the old dialogue, effects and temp music tracks, along with ALL the other music tracks in your session. Then turn on the grid at the frame rate of your movie (probably 24fps) - the editor can’t move picture with any more resolution than this, so do yourself a favour, and do the same.

Then having grouped everything, put the old dialogue track next to the new, and scan through them both by eye. When they go out of sync (the waveforms are different), make a cut and move the whole set of grouped tracks until the dialogue is back in sync. Repeat until you get to the end of the reel, and the pips at the end are back in sync with one another. Don’t try to fix anything yet! You then have a session with (hopefully) some cues moved but untouched (in which case, if you snipped them at bar 1, their new time code location is the new start of the cue), some cues with a couple of 2 frame changes here and there (which you can fix with a minor tempo adjustment), and probably one or two cues which resemble a bar code. Get the untouched cues and the minor fixes out the door ASAP so that your orchestrator has something to do while you’re panicking about the 2 cues which have been cut to ribbons.

Getting sign off

Depending on your relationship with the director and producers (and god forbid, execs). This may be a formal or informal process. However if you’ve got days to go and not one cue has been (in your mind) signed off, it is time to apply pressure from all fronts. This is where your music editor, music supervisor, the line producer or post production supervisor and indeed the producer can help apply pressure that it’s time for people to do their jobs. The director needs to make some decisions and communicate, the execs need to watch those QuickTimes or shut up, and if there’s a problem area there needs to be a meeting booked. Or indeed if these things don’t get done, the whole post production schedule needs to be ripped up to accommodate a score that is far from anchored in the harbour.

But some of this will be down to you too. There is always going to be that pesky theme that isn’t quite delivering or that cue that has never quite hit home with the right emotional impact. Here’s a few tips to getting the stragglers past the checkered flag:

- If you’re on v34 of 1m13 something isn’t working. Instead of adding more thick layers of makeup to your little child, try throwing the child in the canal and making another one.

- Strip it back to something bare and honest, or rely on a solo cello to make good a series of fairly indifferent notes.

- Try going the opposite route to what you or the temp has done (I once replaced a piece of climactic temp which would have had at least 600 orchestral players and choristers pumping away full pelt with a solitary girls voice and a softly played piano which got the hankies out).

- Copy the temp… life is too short, move on and try not to get sued.

The greatest love affair known to film: temp love

Prior to your involvement with the film, someone else has probably put some music on it. Films are a bit weird without music, as you know, and nothing smooths over the unevenness of the early sync dialogue track than a lovely bit of symphony orchestra.

The director probably also played a favourite song on set to get the extras in the mood for the scene, and now can’t imagine the scene without it.

If you’re lucky, whoever put the music on there knew something about film music, was mindful of the probable music budget of the film and only used songs they could positively identify, and which weren’t by the Beatles.

You are rarely this lucky. It’s more likely that someone has ladled the pick of the best film music of the last 30 years all over the film, using an orchestra twice the size you can afford, and for good measure thrown in a couple of Jimi Hendrix tracks too which the director will tell the producer are “just to set the mood while we’re editing, the composer will replace them later”. You don’t want to be “the composer” in that sentence.

Very possibly the worst kind of temp is the kind that has a familiarity. So when it is tested it has an emotional resonance with the listener, not because it is an awesome set of notes, but simply because they’ve heard it before and it reminds them of a nice memory, a good Summer. Or indeed they’ve temped it with one of the greatest pieces of music in a composer’s canon. Elgar’s Nimrod, Debussy’s Clair De Lune. Again, we feel for you. Here’s just a couple of pointers:

- If you see this stuff go on try and get it off as quickly as possible. Especially before it tests. Confide in the editor and say “please don’t do this to me”. Tell her or him you’ll get them something awesome for that bit overnight if they promise not to stick Solaris on!

- When having your first stab at a cue with temp love come out of left field. If you can’t beat the notes, try beating the concept (going super small where they were big can always usher an “interesting” from the loved up director).

- Copy the fucking temp.

Delivering a master to the dub

There are two key factors to the successful delivery of a master to the dub.

- The quality of the assistants at the studios you use to track and mix.

- The quality of your technical prep.

..and we say YOUR technical prep, because no matter how many legions of assistants and tools-ninjas you employ, it is YOUR department, YOUR score, YOUR technical preparation. Don’t you DARE blame anyone but yourself if this isn’t delivered according to a rigid set of principals!

If you’re lucky enough to have the budget and support for such a team we’ve taken the liberty of colouring what YOU need to do yourself in blue. The rest you can shrug your shoulder at and pass along to your unsuspecting interns.

Whilst the music industry crumbles around us and few bands can afford to go to volcanic islands for 18 months to record an album, there is still little evidence that A&R men are asking for a group of musicians and engineers to track and mix an album containing 70 tracks and 80 minutes of material in a single week.

With this in mind, you’re no longer in the music industry. You are in the land of nerds, and you must therefore adhere to our strict nerdlore. We’re here to help, but if you don’t listen you’re about to have the worst week of your life.

Technical preparation

You’re about to enter into a phase of production that I refer to as ‘plucking chickens in a nuclear power plant”. Desperately repetitive, desperately boring, but if you make a mistake it could create a China syndrome for your project. You need to do around 30 odd things to each and every cue, so make sure the process is lean and refined as possible. If your process isn’t refined and takes you 5 minutes more than it needs to on each cue you’re talking 5 hours of precious prep time for 60 cues. Make sure you rest frequently so mistakes don’t happen.

Finally I would recommend you do things in a series of passes. If your flowchart of things to do on each cue is too long you’ll also make mistakes. If it is too short, the load in times will all add up!

One thing I would recommend to start is a vanity pass, to give everything a final check and prep the prep. Each pass gets tiresome we know that from the compositional process, and it’s also likely that as you wrote the score in passes you usually started at the front. So for your vanity pass, start at the last cue and work backwards. Check everything is how it should be then also:

- There is a bar event on Bar #1 (and not before)

- Your cue starts on bar 5 and there is no MIDI info before bar 1

- All your MIDI is normalised (ie if you’ve done any transpositions normalise these)

- Print off your official demo (this will guide your mix engineer)

- Bake a click (MPC Click of similar, no cow bells...)

If you complete this for the entire score you now have a bare bones set of data to work with should there be a fire, a drive error or some other horrific incident!

Now it’s time to perform a tracklay that will organise your data into three key channels:

Orchestrator / Copyist

Tracking

Mixing

Christian has made a film about tracklaying that shows how to prepare materials for the above in both Logic and Pro Tools. You don’t have to be working in the former, it is the basic principles that are important.

The basic headline point is to give people what they need to do their job effectively. So your orchestrator needs audio guidance, MIDI and some brief notes, not a set of multi tracks and a synopsis. Your tracking guys will need a set of playback stems that give you the composer some freedoms whilst you’re recording whilst not burdening them, or their systems with a full multitrack. Finally your mix guys need stuff to work with that balances your vision with how much they can improve it in the time given. The key blocker to your mix will be lack of preparation and an less than completely anal approach to data management.

So the one cardinal rule is, give each track a unique identifier that is matched in the tracklayed audio. This will enable your engineer to drag similar material from one cue to another without being able to pull up and tweak and mix e v e r y single cue. When asked how they can possibly mix 70 tracks in a week the answer is, well they’re not, it’s about 3 or 4 mixes that then get duplicated across the 70 cues.

Session planning

OK, so your orchestrator is fed, your copyist is busy, your tracking studio assistants are busy importing their I/O setups into your playback stems. Your mix engineer is scratching her or his head at the sheer number of “starts”... You can finally relax and jump into that bath?

NOT YET!

Unless you’re scoring a AAA blockbuster with acres of spare time, resources and a team of people who have all laid this stuff out for you. A bit of session planning will be called for. This is to primarily make sure you grab everything you absolutely 100% have to have, that you will get a decent amount of time to spend on it, and that you’ll know if you’re behind or ahead so you can pace the session.

So how much is too much? Well this is an impossible question. But here are a few very broad guidelines:

- Try and reduce the number of ‘starts’ or rather cue files. The amount of prep that goes into making each cue file and the time it takes to load in effect the time you can spend at every stage of production. So one 3 hour session 120 starts…. Never gonna do it. 20 tight, 15 doable.

- The musician’s union in the UK allow around 25 minutes of music to be recorded per session so this should also give you a good guidance on organisation.

- If you have suddenly counted up your cues, clocked up the running time and it is say 60 cues, and 50 minutes of material. Think about halving your band and spreading it over two sessions. I have done this many times and I will simply overdub about 6 of the biggest cues by taking all rhythmic material and recording that in session 1 and all lyrical material and recording that in session 2. This will give you the power of a bigger orchestra that you can’t fudge by getting your players to play the same thing twice once in the first session, once in the second (ie double tracking, which is against union rules in UK). Another thing to do is to just record the bits of the music you don’t think the samples can handle. Long lyrical sections, articulate string lines etc etc.

You may not be having these issues, or indeed, you may (and this often can happen 12 hours before downbeat) you’re about to just find out...

Googlesheet

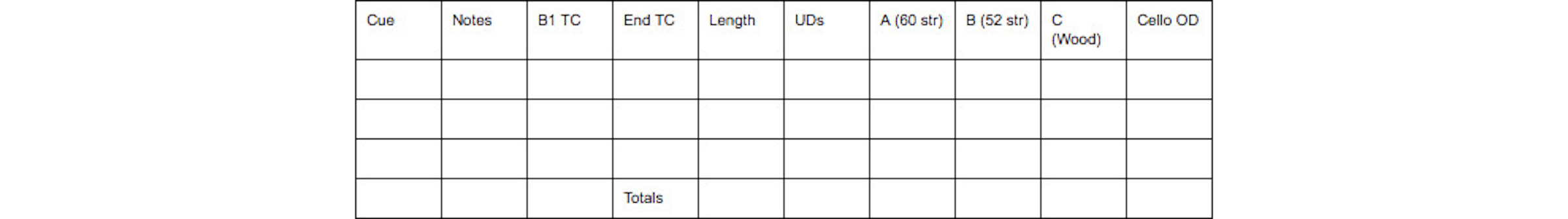

Yes time for another one of those! Or part of the one we did in Chapter One… But here’s what a good session planner should look like.

How’s it looking, do you think you’ll get there? If not?

Pick your battles.

It is a good idea to create an order of play, or at very least the cues you ‘need’ the least, or can just grab a part of. However, if it’s shaping up to be a tough session your engineer can also help make sure things are moving along. The control room is her / his domain, and having the engineer tell your director that you need to move on can often be a life saver. As most engineers do a couple of dozen film scores a year it is wise to save the call to the engineer until her or his mind is really on it. This will be your chance to fill them in on what you’re after, but also the politics of the show. What you’ve been up against, and what you’re all up against at the sessions and mix.

To copy or not to copy

...that is the question and one that should be answered with a firm “NO!”.

It is highly likely that whilst everyone has been thinking about how expensive the studio and musicians are, that the ancillary costs have been totally ignored. You yourself maybe have gone “great 20k, that buys me 15 musicians, for three hours at Air Studios”. But then your music supervisor suddenly hands you an estimate that includes orchestration, copying, a conductor…. “Where did that extra 10k come from?!”. You can scrimp on many things, but if you think copying is glorified photocopying, you’re mistaken. The single most important thing you need in order to record some music is a pad of music to be on the stands, with the pages in the right order, the cues in the right order. If you don’t have this, you don’t have anything.

Live recordings

You need to give the band and your engineer a chance to warm up, test all the lines, the click, the foldback, the mics. So if you start at 1m01 and 1m01 is a 20sec cue when the head pops out of the porthole, you’re going to be rewinding and starting again a lot. It is also likely that the porthole won’t have the requisite variety in material to get your session off to a quick start. If you give the conductor, the players and the engineer a little slice of everything, you’re less likely to have ‘overs’ on the board, and ‘can’t hear clicks’ from the band on 1m02.

So pick a cue that is medium length (say 2-3mins) that has as much variety as possible, that uses the whole band, is dynamic, and offers up some fast, some slow stuff. This should also be your last chance to say… ‘nope close mics not close enough, ambient mics not far enough’.

Try also to NOT pick the hardest cue of the day, or indeed your or your director’s fave cue. Both could offer up buzzkill for you or worse still directors that you may not recover from.

If the only one that fits the bill is the mutha, and personal favourite of the producer’s wife (present), make sure to advise the whole control room that you’re gonna probably come back to it as it is a warm up cue.

Thereafter, if there is a dominant theme or piece that runs through the film I would wholeheartedly recommend selecting the first half dozen cues based on that. You have your director’s attention for the first hour, they won’t bore. So nail the first cue and let the band use their muscle memory to nail as many cues as possible.

The Airbus A380

At first it will feel like you’re no way going to get everything done. You had to introduce the project, that nabbed 3 minutes of studio time, them taking an A another 2mins, the first cue, the test cue you need to come back to took another 4 and then to lay down your first master took 15 minutes so you’re 1 cue down and that’s taken 24 minutes arggggh!

Don’t worry, a film scoring session is like an A380, it takes an age to get going, you’ll think you’re gonna run out of runway, but suddenly it’ll start to hurtle, will rotate and be airborne before you know it.

However...

Pragmatism

The battle we spoke of between the different ‘yous’ will rage greater inside you than it ever has done. Here HOD is king, and producer only comes out of his box when things don’t sound quite right, they’re not working to picture, or the musicians aren’t nailing it, and then he needs to be the fastest producer in the west. But YOU as HOD need to be firmly pragmatic. One recommendation I would have - don’t score read. Get some others to do that, your orchestrator will be doing it if she or he isn’t conducting. I prefer engineers to not read scores either, I like them to listen, but they often insist on it to ride cues. But you the HOD really need to look at the picture. Make sure they have a bar count up on the screen, so if there’a bar that has an orchestration error in it or an edit you want to perform you can shout it out. But just look at the picture and work out what needs to be done for it. Do you really need to re-take that bit, just because there was a chair squeak, even though there is a jeep exploding on screen at that very point? Be safe also in the knowledge that your favourite cue will go from being your sweaty preferred child, to a minor disappointment, and your scraggy runt of the litter will suddenly impress everyone with a surprising set of college results.

The thing I’ve seen time and time again is a composer who has a perfect “show reel” cue. Probably underscoring a gun battle where it will never be heard. I’ve seen composers jeopardise an entire session by sweating a cue that should just have been cranked out. HOD man needs to rule supreme, the producer will hire you again because of your strengths as an HOD, they don’t really give a fuck about the music, it all sounds the same to them.

Use your session planner to move thing along at a steady pace. It’ll give you a good idea of how many starts you’ll need to do and roughly how long each start should take to do. If you move it along and aim to possibly not get to your “up the sleeves” cues, you’ll probably find the session has sped up sufficiently to accommodate them and you’ll finish with everything you need. But you’ll need to be strict with yourself and anyone else in the room who feels something could be done better, having failed to notice that fine textured spiccato rhythm in the violas sits under a mine collapsing.

Etiquette

As music producer you have to guide how the session is going to run. Set a light and humorous tone to proceedings prior to downbeat. Then maybe consider these ideas.

- Prior to downbeat stay out on the scoring stage and shake hands with all the principals.

- Agree with the conductor that he’s one of them and you are the bad guys. You want the conductor to be your mole, rolling his eyes at the bloody control room. He will keep them onboard where you maybe won’t be able to.

- When you get the seating layout from your fixer use a highlighter pen to highlight each section leader / principal so when you need a section to do something differently you can address them by their leader.

- Introduce the project to the band, the conductor, orchestrator and the director if they’re present.

- If the director is present, tell them that you’re going to have to do some heavy lifting, so the plan is to power through and if they’re really not sure about something to speak up (this is going to be difficult for them to do in a control room full of very well trained musos!).

- If the director does ask for something to be looked at and it is tantamount to a total re-score politely say you’ll have a think about how best to approach it and return to it later.

- Musician breaks aren’t a PITA, they’re an oasis of opportunity. If something is wrong with the orchestration and it takes more than 30 seconds to diagnose or fix simply ask musicians to put it to one side so you can work it out in their break.

- If in total doubt, and the director isn’t liking something, stem. Get the musicians to split into sections that you take in bits. This will give you some tools to perform a hatchet job with a mixture of samples and stems later.

- If you’ve written a big solo section suggest the cellist (come on, it always is) offer to overdub in a break or at the very end, so they’re not put on the spot.

- Take difficult or long cues in sections. How do you nail a 7 minute cue in 15 minutes? Well put your little ego back in its box and don’t start from bar 1 3 times when you already have the first 32 bars nailed because it’s so much more fun hearing it in a run. Move through, chipping away and you’ll be at that double bar line before long.

- Samples can save you. Sometimes (I did warn you) you’ll simply need to tacet the pizzicatos and let the samples handle those in order to keep things moving.

And to keep a happy session here are some pointers.

- Congratulate everyone at every opportunity for their amazing skills. Namely what an amazing job your orchestrator has done, what an amazing sound the engineer has got. Include the director in this, such beautiful pictures “I love this movie!”.

- Thank the band when asking them to move onto the next cue. And observe any ‘hole in ones” or particular virtuosic flare with a “bravo”.

- Don’t isolate any individual or section as the perpetrators of any wrongdoing unless there is a specific problem that keeps on occurring at the same point in the score. If there was a split or a fruity note simply go “we’re going to need another x section”. Then you may want to communicate this to the conductor only via his dedicated TB feed. Preface the note with a “This is just to you Jane / John someone in the violas keeps on fucking up bar 13”.

- Don’t tell the orchestra to be quiet, the conductor can do that.

- Try and review cues in breaks or between sessions. There is nothing that’ll comatose a band less than them watching you all waving your arms round in the control room.

At all times keep your cool and don’t panic… take a breath and listen and think. You know ALL the answers, and they’re all in there. Is it really ALL sounding wrong or is maybe just one section at the wrong dynamic? Here’s some common cheeky little fixes to the surprises a live band can bring.

- Pizzicatos are too loose and sound stupid - FFS!!! This is the last time… mute the bastards, samples are fine!!!

- The scene sounds impressive but has lost the tenderness you had with the samples - Ask the strings to switch to mutes, and if they’re already on then ask them to play poco tast (up the fingerboard) or indeed sul tasto. This will take away the operatic sound and give you something more tender.

- It’s sounding scratchy and middle heavy - ask them to warm it up a bit. Or indeed ask the whole string band to divisi by desk ½ as is ½ con sord, ask the muted players to go up a dynamic so they blend.

- The shorts sound scratchy and too detached - ask them to give you a rounder shape, to brush the shorts more.

- The brass is overwhelming the strings - take in two passes.

- It is sounding a bit underwhelming, a bit bored - explain the cue enthusiastically and ask the band to ‘play out’ or ‘molto espressivo’. To give it ‘all they’ve got’.

- Invitations work better than instructions. Instead of trying to tell the players how to play their instruments invite them to contribute by saying things like “I need this section needs to sound a bit more haunting”. You’ll find this works better on strings than say trumpets. I once asked the latter to play with a more ‘distant’ sound, they looked at me blankly and retorted “what, quieter?”. If you have time to invite a principal or the leader into the control room to talk about a section you may find this really reaps huge rewards.

Mix planning

You mix session will share the same need for preparation that your tracking session will need. If you have a chance to perform some additional technical preparation between the tracking and mixing this will be time well spent and money saved!

Organising and comping (performing edits between preferred takes) all of your live work into the same Pro Tools sessions as your mix prep, muting the samples you don’t want to use and creating a general balance that you’re happy with so your mix engineer can pull the faders up in unity and not go “WTF?”. Will be a great help. Whilst your mix engineer may be a Pro Tools ninja, it’s really not her or his job, so a day between the track and the mix can be an awesome way of assuring you get the best out of your mixer.

You’ll then need to organise a ‘mix schematic’ so your mixer can chart her or his way through what needs to be done and how best to do it.

Genetics

Here’s a suggested sheet (which could be part of the same sheet as the session planner)

Whilst most of this table is self explanatory, it is an instant colour coded visual aid to you and the mixer of how things are going and what tasks lay ahead. How many shortish cues there are to do, and when starting a new cue, by using ‘genetics’ as a guide you can pull up a previous mix from the same gene pool. So you’ve approved the love them at 1m02, your mixer will then start mixing 1m05 by using the mix session from 1m02. This will speed your mix sessions up in a way that is similar to the A380 comparison we made earlier.

Mix session

The other reason for making this chart is so that you can LEAVE THE MIXER TO IT!!! There is nothing worse for your objectivity than hearing a mix engineer break your lovely sounding score to pieces before reassembling a sonic tapestry that will be close to what you were imagining. So set times with your engineer where you will come back and listen to approve some mixes.

Panic Kneejerk Buzzkill Syndrome

When you do return don’t fall into the PKBS trap, aka panic kneejerk buzzkill syndrome. You immediate reactions to mixes will be confusion. What’s different, why…. Urm…. what?.... Argh!.... Argggggggghhhhhhh!

But be cool. In my experience if more than one thing is off it becomes daunting. Take a deep breath and figure it out. Does the mix sound totally wrong or is it just too dry and the woodwinds are too loud? A good way to look at it is to reverse what you don’t like and analyse what you do. So if for example the whole thing sounds ‘fucked’ but the woodwinds are the right level and sound great, maybe in fact the woodwinds are too loud and the engineer needs to copy across whatever he’s got on the woods on the rest of the live stuff.

If she or he has worked themselves into a sonic cul de sac listen to a few cues and quietly work out in your own head how many invitations to give them versus instructions. So with the former:

“I’d like it to sound more live, like the players are all in the same space, that there is a sense of distance and depth”

...and the latter

“More reverb on everything, can you place a shorter hall verb with lots of early reflection on the flute overdubs, turn it down, pan it, and send it to the back of the room with lots of the main verb”.

Common ‘mistakes’ engineers make:

- Having personally been involved in the live orchestral recordings and not the demoing process they will feel a natural alignment to the live or orchestral material. Say that you have had the director sign off on these cues weeks ago so you would like her or him to start each cue by listening to your demos. A common engineer complaint is “I’m really not getting this cue” if they listened to the demos they would!

- They will sit the ‘fakes’ behind the real instruments. You need to tell them that even though the horns are sampled and the strings are live, the horns still need to obliterate the strings as they would in the real world. Suggest also that instead of putting the samples behind, that they simply rest the orchestra gently on top, like a glowing sheen of reality over the thudding forces of your hybrid orchestral score!

- They won’t use enough reverb. Once this stuff sits behind a perforated screen, dialogue and atmos tracks containing lots of white and pink noise your cues will sound more arid than a drunk’s tonsils. Insist on lots of reverb and explain the aforementioned sample issue with longs versus shorts.

- They won’t make it bright enough (see previous bullet point).

- Using LFE as part of their bass management system. You need to command them not to do this. If you don’t, the dubbing engineer will take one look at your LFE track and say “fuck that” before hitting “cut” on his desk. This means your mixes will lose all their bottom end. Make sure this is all managed in L&R there is very little info save some verb bleed in C, Ls & Rs contains very little direct signal and the LFE is just Low Frequency EFFECTS. So an occasional taiko boom. Maybe a sine wave an octave under the basses for a key moment, but that’s it!

- They won’t turn it up by how much you tell them. Reassure them that you spend your life turning up and down faders in the box so really understand what a db sounds like, and when you say up by 1.5db you mean it, even if it is imperceivable, and when you say up by 24db for the cello, you really do mean eight times as loud as it currently is.

- Faff around with too much fiddly faffy stuff and not just get on with it. Your samples (we hope) are world class, the recordings are tip top, everything has been organised, you’re happy with the general unity mixes being pulled up. “Whack some top end on, tickle with some compression and make everything wetter than a drunk’s bladder and move on!” The deadline will not move, you may get stuff sent back from the dub to recall, c’est la vie!

Preparation for dub

Preparing for the dub comes down to one thing really... how many stems should you provide?

Once upon a time you recorded an orchestra in a room, delivered your mix on magnetic tape then went to St Tropez for cocktails. Also, once upon a time “locked picture” had some meaning. Neither of those things are true any more. So you need to make stems.

In the reasonably recent past, there was a technical limit to the amount of tracks a Pro Tools rig would play back, and you were limited to probably 4 or 5 full 5.1 stems (allowing for 2 sets so that you could overlap cues). Nowadays (and within reason), there’s not really much of a technical limit. It’s perfectly reasonable to have 2 overlapping sets of 12 x 5.1 stems, plus a few extras for the stereo source music, and a few more for dialogue, effects, AAF tracks, temp music guides plus the video.

So what are the arguments for and against multiple stems? Well, traditionally the main argument AGAINST making stems was that it would give the director the opportunity to “mess with” the composer’s finely crafted art. Composers believed that if they delivered a single full mix with no options, their artistic integrity would be maintained, and the director would humbly bow to the composer’s superior judgment. The problem with this is that the director WILL mess with the music anyway, and if there are no stems, and they have a problem with something, they’ve not got much choice besides turning the whole thing down until it’s nearly inaudible, removing it altogether, or asking someone to create a new “Frankenstein” cue out of a mish mash of others. If you’re lucky that someone might be a music editor.

So here are some dos and don’ts for creating stems:

- You might end up with more tracks in your session than there were in your multi track. This is OK (though don’t suggest to your engineer that the opposite of “mix down” must be “mix up”).

- If you have orchestral separation, use it!

- Separate low and high percussion. There are literally no circumstances where you will want to do the same thing with a suspended cymbal as you do with a bass drum.

- Make sure anything you know to be controversial, wacky, or “comedic” is separate.

- Likewise, separate anything which the director (editor, producer, etc) has expressed any uncertainty about in the past.

- Remember, that one of the principle reasons for stemming is to give your music editor (or you!) half a chance to re-edit a cue if there are big picture cuts after the recording is over. So keep solo melodic lines separate from the orchestra where possible and also consider separating melody from counter-melody.

Deliverables

At the end of the dub, if you’re not fortunate enough to have a music editor, you’re going to receive an intimidatingly long list of things you need to send to the production. This will include the dreaded cue sheet, as well as copies of all your cues “as dubbed” in addition to “as recorded”. We’d encourage you to let the music supervisor fill in all the details of the source music on the cue sheet (to which end, we would recommend you use a Google Docs spreadsheet so there’s only one document to update, not a constant string of emailed Excel spreadsheets). To get the timings you’re going to need a copy of the final dub music stem from the dubbing theatre. Measure the duration from the point the music becomes audible, to the point the the tail of the final reverb becomes inaudible. Round up to the nearest second. If they’ve cut a hole in the middle of your cue, our advice for when to split it would be “don’t take the piss”! A 2 bar gap to allow a line of dialogue through is OK, a 1 minute deletion means this is now two cues!

Delivery requirements documents from even major film studios don’t seem to get updated very often. If anyone mentions putting the dub on DA-88 tapes, tell them to stop being so silly. Hard drives with Pro Tools sessions on are fine these days. You’ll probably have to make CDs though. To which end, it’s worth making stereo mixes during the mix sessions, and having the assistant engineer top and tail them and make 44.1kHz / 16bit files as they go, rather than doing it yourself in one go on a total downer at the end of the gig.

Conclusion

We hope these articles give you an insight into the world of film scoring, and for some possibly some valuable guidance… Hopefully steering one or two of you clear of the pitfalls we have already fallen down. Technology changes, so this may become a relic of its age in a few short months! But at the heart of it, the sentiment will remain the same. It is a vastly complex business, with vastly complex people hustling vast egos, with vast expectations. But when done well, with the right people and on the right project, can be one of the most rewarding professions in the world.

If there was one parting thought we want to leave with you, that would be; don’t ever think you’re going to arrive, because if you do there will be nowhere to park. It is all about the journey so make sure you’re topped up with fuel, you’re in a comfortable car, you don’t have a map reader in the passenger seat that you know is likely to be hell on highways, and make sure you don’t fall asleep at the wheel. As a session guitarist once said, “this is supposed to be entertainment, we’re not at war”. No one knows which job is going to break them, which relationship will flourish, which score will earn you that Ivor Novello. So instead of looking out for those things, why not look out for experiences that will nourish you, work with people who enhance your life not drain it, and make sure that your life is rich away from your digital audio workstation so that your work reflects the human condition, not that of a poorly conditioned automaton with a greyish-green studio tan.

We don’t smoke cigarettes because we know they are bad for us. We don’t eat pizzas for every meal because we know it will make us fat. The same should be made of our mental health, don’t knowingly put yourself in harm’s way. Whether that be with agreeing to an impossible schedule, or by knowingly venturing forth into the pathology of a bully. Enjoy the journey because that is all it is, and please please look after yourself whilst you’re on it.

James Bellamy, Christian Henson & Paul Thomson