Scoring A Film: Part Two

Members of the Spitfire Team with a few “Movie Miles” under their belts collaborate to define the best way to approach film scoring.

What you need from the cutting room

No matter how experienced your editor, or editor’s assistant, they will never know what the music department wants or why. You’ll need the picture, you’ll need the dialogue, and you’ll need them to separate their temp score from this. If they don’t separate the temp score you won’t be able to work against dialogue which will mean the mother of all bun fights at the dub. You should also request some onscreen sync ref… Here’s what we recommend:

Audio

Embedded into your video file ask for:

- Left channel: Dialogue and effects (the assistant editor will often whack in a few smacks and whacks, gun shots and explosions, make sure you get everything they have so you don’t confuse the director when playing stuff through with her / him).

- Right channel: Temp Music

Additionally, ask for separate timestamped WAVs (@ 48kHz / 24bit) of:

- Mono dialogue

- Stereo Effects

- Stereo Music

The absolutely critical thing is to get the temp music by itself so that you can get rid of it when you need to.

As the music editor, I also ask for the music AAF output from the cutting room so that you can read the track names of the music files being used (so you can see whether the cutting room has bothered to put in all the cues you’ve been sending over all week).

Picture

H264 compressed picture offers the best tradeoff of resolution versus size, and this seems to be the format most cutting rooms use these days. On a typical modern feature you’ll be getting a lot of versions of picture, so even though disk space probably isn’t an issue any more and the internet is fast, you still want reels to come in at a sensible size. 4-5 Mbit/s target compression will usually bring in a 20 minute reel under 1GB and still looks great (and means you can download an entire 8 reel movie in under an hour on a reasonable internet connection).

The video should have

- A standard 8 second (12 feet) leader.

- Sync “plops” 2 seconds before and after the reel (with accompanying pip in ALL the sound files).

- Burnt in SMPTE time code * on screen (aka BITC, Burnt In Time Code)

- Burnt in feet + frames (standard time reference in the US).

* SMPTE (Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers) time code is a standard way to label frames on a piece of video or film. It takes the format HH:MM:SS:FF (hours, minutes, seconds and frames). On a feature film, each reel traditionally begins at the hour of the reel number (eg. Reel 1 starts at 01:00:00:00, reel 4 at 04:00:00:00, etc). The number of frames displayed will depend on the film / video format. Film has 24 frames per second, PAL TV has 25fps and NTSC 30fps (well, kind of…).

A quick note about NTSC

Mercifully, most video files for film work are now output at 24fps so you won’t need to worry about this problem. If you are in the world of NTSC video (on a US TV series for instance), you should make sure you do an end to end sync test with the cutting room as soon as possible to ensure things will stay in sync later on. The settings you will need to use depend, to a certain extent, on decisions the on set sound team, and post sound team will have already made before you start regarding sample rates, use of pull up / pull down. Consequently the sound team are usually the best source of advice on what to do. It’s worth getting a book and struggling through the maths at least once before you tackle NTSC.

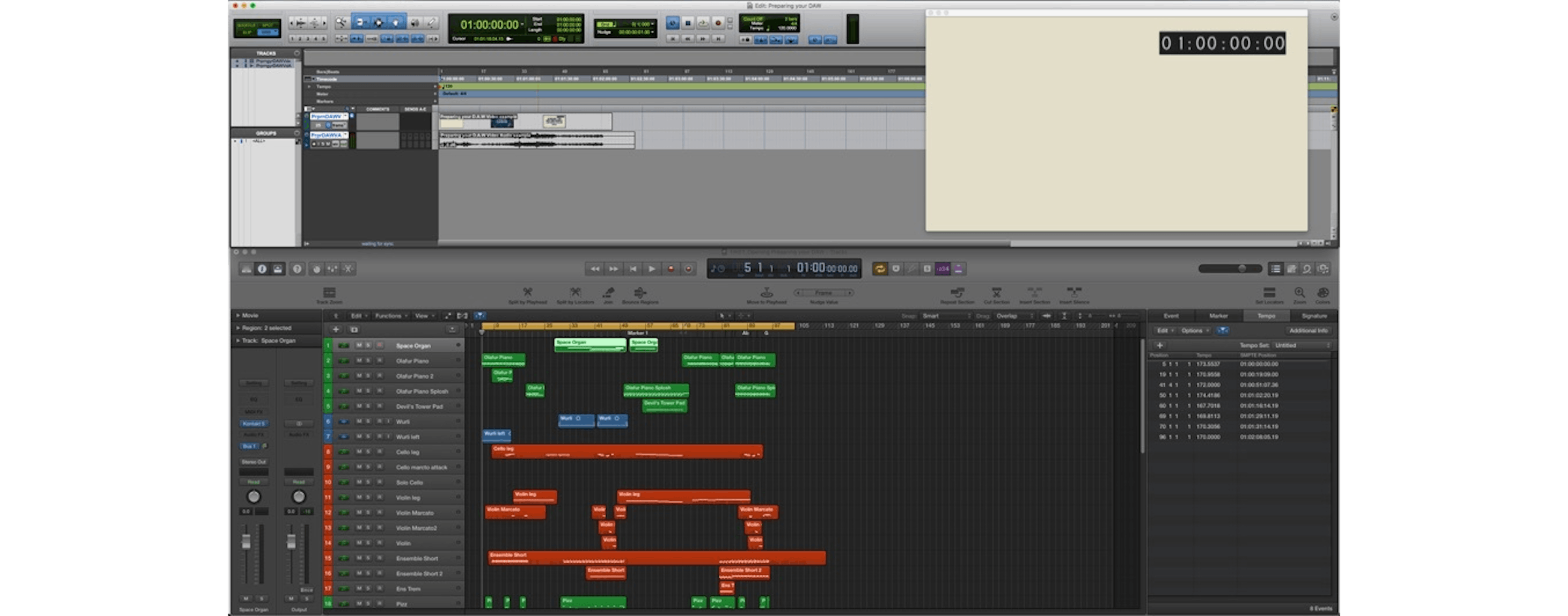

Preparing your D.A.W.

Regardless of your sequencing D.A.W. we strongly recommend running picture, dialogue and your own bounced or baked demos from Pro Tools. There are a number of reasons for doing this. Initially so you can run your draft cues into this and instantly hear incoming and outgoing cues bookend the cue you’re working on. If you do this as you go it means you will also have a presentable single preview cut to view yourself. So sit back and check a reel. Pro Tools also allows you the brilliant facility of having all reels in the same session, this again allows you to jump around the film, in a single file, on a single timeline. So watch the entire film with the director to get a real sense of thematic arc and balance. The other very technical argument is that you only have to set up your PT session once, and once you have checked this with the cutting room, your own PT session will become an immediate sync check so that you can trust files are being sent along to the cutting room or director with the correct idiot-proof timestamp, or the even more idiot proof Pro Tools session! If you get this all right it will also be what you end up using to send to the dub, whether it be for temp ‘preview’ dubs or indeed the final mix. They will much prefer to receive a Pro Tools file from which they can extract what they need as opposed to a bunch of stems that they have to spot in themselves. If you have never used ProTools this is EVEN more reason to adopt. As the only industry standard piece of software there is, not knowing how to use, nor getting your team to adopt it, will frustratingly stymie your interaction with the rest of the sound department.

First of all make sure your session setup is at the frame rate of the movie you’re working on.

Pull in the files sent to you by the cutting room reel by reel (sometimes if you’re brought in early enough it won’t be separated into reels), making sure to import the audio (if embedded in the video files) along with any extra audio files or data. Pull the videos onto your timeline and click on the first frame, hit spot and dial in the onscreen BITC or SMPTE of the first frame. Then match the spot of the video with the audio extracted. Selecting the video then control-clicking the audio to snap to start is the easiest way. If you have the dial / FX / temp music as separate WAVs, you can spot those to their original time stamps (and check they match the audio you extracted from the video).

It is then worth going to the first ‘live’ frame of picture for each reel and create a marker for picture start on each reel. Which you would expect to be on the hour of every reel (but might be 8 secs later as some cutting rooms start pre-roll and leader on the hour). This will allow you to quickly skip between regions that are literally hours apart, or indeed splice together the movie in a matter of minutes for a preview (it helps to mark the reel END as well for this - not the pip but the first frame of black).

If you’re throwing your image onto a TV screen be sure to adjust the video offset according your TV’s tracking speed. My projector is 5 quarter frames, which is not insignificant. You’ll then need to set up two audio tracks for every stem you’re going to provide… Which will probably be a simple Full Mix A and Full Mix B in the initial stages. You need two tracks because your cues will often overlap, even if it is just with pre-roll and count ins. So you’ll need to ‘checkerboard’, and your sound department will understand this.

Preparing your D.A.W. for your first cue

So if you’ve followed our advice and have your picture running from Pro Tools, you’ll need to work out how to sync your picture playback D.A.W. and your sequencing D.A.W. If you’re using a devoted or (somewhat horrifically named) “slave” unit to run picture then a simple MIDI cable will probably do the job (if you can be bothered with user manuals, you can even use MMC - MIDI machine control - for this so the sync is instantaneous). If you’re running both PT and your sequencing D.A.W. from the same computer (perfectly doable these days) then you’ll need to sync via some IAC driver… All of these scenarios are amply explained on the interweb.

As with your picture playback make sure your sequencer D.A.W. is set to the correct frame rate. It is at this point that establishing a harsh sync protocol is well worth considering.

Whilst it is fairly easy to get your picture D.A.W. to lock, and it maybe fairly easy to diagnose sync issues in these heady early days. Once the pressure is on and your 50 or 60 cues in and there are stems, and multi tracks, and pdfs with scores flying around, and there is a conductor scratching his head in front of 40 glum players with a picture that is the wrong point of the cut and a violin section that is a 16th out with the drum stem. You may think differently about the importance of establishing strict protocols so you can immediately remedy these likely creases caused by human error and snow blindness at the end of a very complex process. With rigid protocols you can instantly spot if something is not quite right, and more importantly, spot it weeks, days or just (but precious) hours away from your sessions.

I therefore recommend that your cue always starts on Bar 5. This will allow a bar of lock in time, eight beats to your conductor and then eight beats for him to bring the band in on. It will also allow plenty of time for all controllers and keyswitches to be zeroed (when bouncing from bar 1, many sequencers won’t trouble themselves with observing what zeroing and key switching you have done prior to bar 1 even if they allow a pre-roll to bar -8). You must always also bounce or bake all of your recorded material stems and mixes to bar 1.

If you have a key frame to hit that’s gonna be way into your cue, so preamble preamble preamble, head comes out of porthole, cue starts for real, panic panic panic!!! You may want to sync your cue to bar 100. Write the cue, do the preamble, then count back four complete bars from your first beat 1 say that is bar 72, then delete what is between your current bar 1 and bar 72 so that you’re new bar 5 is the start of the preamble.

Do this and the teams handling your material, the guys at the recording sessions, the dub, the cutting room, your orchestrator and copyist. Will all know one simple thing, cues downbeat on bar 5, data starts on bar 1.

Getting the tempo right

This is something that comes with time. It isn’t to do with hitting cuts, it is to do with the natural pace of the scene or sequence. It is something that can’t really be taught, you’ll just get a feel for what is right and what is wrong.

If however there is a very key meter or tempo change mid way through a sequence. So for example’s sake say there’s a scene where they’re plotting on how to blow up the houses of parliament in hush hushed tones, then suddenly the police burst in, they’ve been rumbled and so follows an action chase sequence. It is probably worth splitting this into two cues, or rather sub-cues.

So 5m63 Plotting vs Chasing Sequence becomes 5m63a Plotting vs Chasing Sequence pt i and 5m63b Plotting vs Chasing Sequence pt ii. It’s completely up to you how you split cues up, and with our fantastic frame accurate digital software we can be sure to make completely crease free cue switches. It also helps to break up the ‘long action sequence’ frog into more palatable morsels (more of that in a moment).

If you have time both at the front and end of a project to work without a metronome then we truly believe this is the best way of working. Provided you have a good sense of your own compass, slow free-styled cues that weave around the dialogue can be amongst the most expressive and satisfying work you can create. Remember though that at some point this stuff will have to be clicked, so have empathy for the craftspeople at the other end!

Laying your first cue

Once you’re happy with your first effort it’s worth laying it into your Pro Tools session. If you’re really clever you may have it bussing through to your Pro Tools sessions, with all sorts of mix stem busses setup, playback stems, orchestra stems and click tracks. So with a single press of a button you could theoretically have an orchestra playing it within the hour.

HOWEVER, no matter how much a director loves my work and may feel I’ve hit a hole in one, there is never a time where after a first pass I don’t want to make some improvements. This means I lay down what I need for now, safe in the knowledge that I’ll need to return to tidy up, and check everything.

With this in mind I simply bounce offline the full mix and then bounce a click (If I’ve set up the template right I can do this simultaneously). This will mean I’m ready to go for a pre-record or an underdub as I call them, if I need it. If I’m expecting to do a whole bunch of pre-records I’ll also have playback stems pre-routed so I can bounce those too in a single instance. Playback stems will be the whole (ROM or Rest Of Mix) then a separate stem for each instrument or group of instruments I’m likely to pre-record. So say I’m going to underdub some vocals, a solo cello, we’ve got a big string session and then an Oboe overdub session. I’ll tacit (or mute) these four elements and run down the ROM track, then I’ll solo each of these elements and run down a dedicated stem for each, I’ll finally run down a baked click track.

So back to bouncing… whack your time bar onto bar one (note the TC of this) and bounce, with the project code - cue code - and version number. It is important that you then save down your D.A.W. file with the same version number so it correlates. (I’d then suggest you move the previous version into a folder named (old cues) within the film project folder.

Once bounced pull it into Pro Tools and spot to the time stamp… Make a marker in pro-tools and paste the TC noted into this, give it the cue code identifier. You should now have a cue in the right place in Pro Tools, sync’d with its correct time stamp. The left hand edge of this cue should be right against the marker because you have the correct TC noted, and your sequencer and picture D.A.W. are all on the same page, in one fail swoop you have triple checked your own sync integrity.

Now when making more stems, even multi tracks for your cues, always bounce from bar 1 (even if it is 15 mins of silence with a cymbal crash at the end) that way as you build up your data pool of stuff for your film, things will instantly look out. Whether it be a poorly aligned region, a region that ends early or starts late, a score that has the first beat of music on bar 6 not 5. By heading to achieve these painful consistencies you will be able to identify the problem immediately and in times of extreme stress when you have 90 odd musicians staring glumly through the glass at you as the sound of hundreds of pounds being flushed down the bog fills your exhausted tinnitus-filled inner ear.

When it comes to labelling the files you’re going to send to the cutting room, file names should include a minimum of the following if you don’t want the assistant editor and your music editor to hate you:

- What film it is (abbreviated, e.g. MA2 = Massive Apocalypse 2)

- The cue ident (eg. 1m01)

- Very short descriptive title (e.g. ToadHall)

- The date (formatted YYYYMMDD so that cues sort in your folders by date)

- The picture version (this is of near biblical importance, don’t label any file, EVER without the picture version, whatever the (so-called) lock status of the cut may be)

- The spot timecode (it’ll be in the timestamp of the file, but a useful cross reference)

- Your own version number (v1, v2, v3, possibly include your initials)

- Some indication of what the file is (FullMix, GtrStem, FullMixNoCymbl, etc...)

A good file name looks like this (NB underscores are better than hyphens, which are used in these examples to keep this site intact on mobile devices!):

[MA2]-2m07-BadEgg-20160927-R2v27-[2.8.9.16]-CHv3-FullMix.wav

If the picture cut moves to R2v28 and the music editor is going to fix the cue, they can then call it:

[MA2]-2m07-BadEgg-20161001-R2v280[2.7.59.18]-CHv3-FullMix-JBConform.wav

Yes, we know these are very long names, and boring to type. You will thank yourself later, however, when you hear something you dimly remember and think “what is this?”

Eat the frog

We’ll let you research that phrase. But attack the bitch cue first. Well don’t. First attack the cue that made you really excited the first time you took a look at the show… The bit you just knew how to nail. OK, that’s in the morning, now in the afternoon, find the bitch cue and attack that…

Charcoal sketching

The end of the day will be your most truly creative. You’ll be in the moment because you’ve done everything you needed to do. So before pulling down the shutter… and especially if you’re eating the frog with the bitch cue, perform a charcoal pass. This is literally smacking the keyboard, little melodic noodles, mistakes everything. Literally run that cue down a couple of times and improv, until you feel that the destination for the cue is due the compass point your sketch is pointing at. This will mean that tomorrow morning, you will wake up about to attack the frog, eat the bitch, and you would have slept and processed it, and you will (because you’re an awesome creative type) be bursting with ideas on how you’re gonna orchestrate that bit, how you can Q&A that melodic noodle you placed here, there and what you’re going to use to pad the whole thing out.

The frog is a big rough toad

Break the bitch up into several cues… The temptation with a single 20min cue is to go to bar 1 (or ahem, bar 5) hit play and run it down. You do that three times, you’ve lost an hour… Some things are better handled in smaller mouthfuls.

First pass

So you’re officially out of the procrastinarium. It is worth talking very briefly about the different jobs we do and how those jobs take up our time throughout the process.

You are a composer, a music producer, and a D.A.W. / programmer ninja pretty much all of the time. You’re also depending on you, your setup and the job, an orchestrator, arranger, musician, music editor, music mixer. Let’s for now just call this Head Of Department… Which basically means someone who has to get the right shit, at the right quality, to the right person at the right time.

So when your job starts you’re a composer salesperson, talking tossily about music what it means to do and what you’re gonna do with their film. You’ll then have done some themes which will mean you’re a bit composer, a bit record producer, a bit D.A.W. ninja. Then as you pass through the movie you’ll start doing less composition first, and more production, then you’ll be doing little to no composition and a lot of production, until all you become is a D.A.W. ninja and an HOD, until that big day when all you are is a music producer through the mix at which point all you’re left with is a dry and addled shell of an HOD.

If you follow this plan it is worth playing to the strengths of the position that dominates and is appropriate to the timeline. So there is no point in storming into the dub going “I’ve just composed a better love theme stop everyone stop!” that time has passed. Conversely if you’re on the scoring stage knowing full well that you’re not going to at the pub that evening but staying up late trying to find that all important love theme before your final session the next morning, would suggest to me you didn’t make the best of the time laid out when you should have been composing.

...and for me the most common, biggest single inappropriate and most dangerous time soak on any musical endeavour is letting the inner Trevor Horn come out and overcome the process. That is you as the music producer. There is never a time when a “we would have finished writing that hit had the producer managed to really nail the hi hat sound” is EVER appropriate. Know thy place. Movie first, appropriate notes, working appropriately around the dialogue second, hi hat sounds last. That includes hitting cuts and auditioning every pad sound you have in your Access Virus TX, just in case you missed “the one”. Just get on with it.

For me the best way of balancing composition, production, and implementation is to perform a series of full passes of the score. This will also give you the opportunity to exercise your part in the story telling. Making sure the thematic arc works and that there is a good balance of themes, and not too much music. Though it may take a while to get up to steam on this I would suggest one reel of music every two days. Which on an average film is around 10 mins of music every two days. You should be able to handle between 10 and 15 mins a day. This isn’t by being a magician, it is by being pragmatic in your approach. Balancing detail and craft, the dreaded ‘inner Horn’ with the need to get from A to B.

So for me with your first pass should be a week and a half. Ask the director and producer to give you two weeks before they come and see your first efforts. This should give you time to fix some immediate howlers you’ll notice when playing it in a run to yourself. Time to have a shower, and time to buy some decent biscuits.

Pre-records / Underdubs

The sooner you can get some underdubs under your belt the better in my humble opinion. Your music supervisor will hate it, your accountant will roll their eyes at it. But the sooner you get some original 100% unique human material onto you score the easier it will be to sell. Is it a gamble? Well yes, if you feel that money spent on stuff that may end up on the cutting room floor is not well spent. Is it a gamble if it adheres your director to your approach and angle and in turn, score? Then no, I don’t think so.

I guess for me the best example was a director “doing a Terence Malick”. So I was faced with the eponymous field of barley blowing majestically in an early evening dusk. An arid, and heady scene. I knew the director loved this shot so wanted to give him something unique to accompany it. My solution was to raid my piggy bank and book 25 mandolin players to perform very slow tremolandi in the Hall at Air Studios for two hours.

Was the sound spectacular, well to me yes, such an obscene number of people playing really small guitars in a large space. To the director was it amazing, well no and yes, no because to him it was just a sound, but it was a sound he’d never heard before and it matched the image perfectly… and when I told him how I made it… I gave him something tactile and tangible to hang his hat on. Thing was our relationship deteriorated over the following three months. He’d directed a good film, and I delivered a good score, we just didn’t like each other very much. But I knew I was never going to get fired because I’d gifted him a good sound over an average shot that he was proud of because it made him feel like Terence Malick The 2nd.

The truth of the matter is Directors will often fall head over heals with your underdubs because it will be a single player embodying their vision in a way they can connect to. You will have rushed it, and they will love the rawness of it. It may be your next door neighbour, and you have every plan to replace, but they will LOVE IT, they’ll love that story, it’ll mean they can talk up the score on their junket.

With this in mind make sure you always approach every underdub or prerecord under the presumption it will make master. If you score is 5.1 make sure you have made a provision for that. So don’t sling a Sure SM58 in front of your hot neighbour who you always wanted to find an excuse to invite round with their cello. Record it properly with a stereo room mic you can ostensibly feed into a surround feed.

Nothing gives a sound department greater pleasure than you recording something that the director is literally having wet dreams about, only for them to say “well we can’t use it, it’s out of phase, it’s full of CPU noise and sounds like an SM58 was used to track it”.

Other people’s pre-records

But what if you have no choice but to integrate into your own score someone playing an instrument on set / something the previous composer wrote / the producer’s baby daughter “singing” / the gear sounds of the director’s sculptor mate’s steampunk mechanical creation (to choose some real world examples that have happened to us...).

Here you are faced with two choices, based on the answer to the question “is this recording usable in a feature film”. Our advice would be to find out the answer to this as definitively as possible at the earliest opportunity. Don’t take the editor’s word for it that a higher resolution WAV exists until it is on YOUR hard drive, and you’ve heard it with your own ears. I was promised an “original WAV” throughout the duration of post on one film, only to discover with a day to go until the final mix that it had been recorded by the leading actor in his bedroom on an iPhone.

If the sound was recorded on set, you at least know they used a decent mic, and furthermore, your film’s sound department will have had a world of experience removing shash. It’s highly likely that they’ll be able to salvage it with a pass through izotope RX or similar. You can then get it back in tune with Melodyne. Then you get your music editor to tempo map it, chart the chord changes and you’re in business. You can even do clever stuff like using the on screen sound to set your tempo or sampling a small chunk to make rhythms from. This all makes you look good, and isn’t as difficult as it sounds like it would be.

If the recording is NOT usable, is distant or riddled with irregular clunking noises or wildly out of tune, you need to tackle that situation head on at the earliest opportunity. i.e. You need to replace the recording with something better, and the sooner you do it, the sooner the director will get behind the new version, think re-recording it was their idea, and grimace at the sound of the original. If the recording is used in sync on screen, you’ll need to get it tempo mapped and transcribed, and pack your music editor and a musician off to a studio to get it painstakingly re-recorded (or if time is tight, do it himself in his cutting room one note at a time on an instrument he can’t really play).

Ultimately, the trick with pre-records is to sell whatever you’ve had to do as a positive move, not a rescue attempt (particularly if it’s the producer’s baby daughter).

Notes & recuts

Whatever you do, if you’ve never worked with a director before, try for God’s sake to get them over to your place to watch a first pass, or part of a first pass rather than sending them QuickTimes of individual cues. At this stage the director may have time for this, he may not have later…. This is your bonding opportunity.

If you send him QuickTimes, he or she will not look at them until very late into the evening, when they’re tired and have two large glasses of claret inside them. At which point they will listen to something they don’t understand, doesn’t sound like the temp, doesn’t sound like what they were imagining, is too loud for dialogue, is on a really small file size with awful compression that makes their 35mm look like a 1980’s camcorder, and won’t be as up to date as the cut they worked on about 45 minutes ago. They will, through nervous exhaustion, panic and inner frustration, pour forth bucolic venom from which you may never recover. So for god’s sake man, woman, get them round, even if it’s at 10 at night, pour them a large glass of really good wine, hand them an enormous plate of grapes, and fill their world with loud, bassey, cinematic music.

But let’s step back and prepare for that moment.

So here’s the thing. If you’ve done a full pass in two weeks you’re going to be tired. You’re going to be really eager to show the director everything. Really eager to say “it’s all done, let’s watch your movie”. Don’t make a mistake I have fallen into time and time again.

When the director and / or producer arrives, just say that it has been going well, and you’re loving the film… If the editor is there say how easy it is to fit music to their cutting style… and thanks for the temp it was a huge help. Don’t say this in front of the director, pull them to one side and confide this in them… You’re one of the crew, just like them, high five man, good job. Editors are very easy to get onboard, and YOU WANT THEM ONBOARD.

So you’re gonna need to read this like a Jedi. Don’t tell them you’ve finished their film because you haven’t. Ask them how much time they have, and how they’d like to look at it. If they say I don’t know, suggest you watch a reel together in a run then maybe go back and take notes… This means if it turns out to be agony, everyone knows its just 15-20 mins of agony! You can also just suggest skipping through any bits of the film they’d like to get an over-view. This will impress them, you’ve done a pass, in some shape or form, but you’re not suggesting “its’ done”, which of course it isn’t.

What will not impress them is force feeding a score that is no way nearly hitting the mark down their throats. They’ll find the process unbelievably painful if not insulting. I have done this on several occasions and it has never ever ended well. I remember one director sitting next to me who squirmed each time a certain theme came on. I knew when that theme was next up, so I’d know when he was next going to squirm, reel after reel of retching in his own armchair. But I couldn’t switch the thing off, he had the remote control! This is why you need to be in control of the situation, you need to be at your place. You need to learn immediately if:

- The director likes to monitor loudly

- The director really needs to hear dialogue clear and crystal

- The director has the patience to work through stuff that is maybe 50% there.

- The director is running out of steam, patience, or the will to live.

Conversely if he’s loving it, jumping up and down with excitement. Run the whole show, you can then let “the Horn” out for the next few weeks to nancy with some hi hat samples!

But in all honesty, something that is pretty much guaranteed is you’re going to take notes. If you don’t have an assistant or a music editor I strongly urge you to get a friend to do this who doesn’t mind being called your assistant and keeps their mouth shut… If it’s a music editor, invite them to contribute. But no talking from anyone who really doesn’t know WTF they’re talking about. Tell your friend if they ask them anything to say “I’m too busy taking notes, I’m not the person to ask...”

You can take notes yourself but it will disengage you from the director, and from their film. You’ll find they’ll keep going, no wait, can you just look up so I can show you the bit I need you to hit… this they will find annoying, like you’re not paying attention.

When you take notes, or have them taken for you write what the director says, not what you feel, or what you feel the solution is. The director will want you to refer to what she/ he says, not how you reacted to it. My recommendation would be to take the notes away and re-watch the sections you covered asap and fill in a second set of notes with what you’re going to do about it. This will give you precious bath reflection time when you can think how best to approach the issues at hand.

For your first session with a director keep Mister Argumentative Ego Man in his little box. Let the trust grow, but most importantly approach this as a brilliant music producer would. To quote Rick Rubin “don’t judge an idea on how well it is explained”. Listen to the director, don’t try and second guess and where she or he is struggling, offer your feelings. If you’re not a raging egotist you will also probably say, “you know it wasn’t until watching it with you did I feel what a stupid idea that was…”. If the director is really pulling her or his hair out, say “it’s cool, let me just take another look at it.”

Rejects

Unless you have experienced childbirth first hand you will understand that the inner turmoil, the struggling in the late hours, the agony of self doubt creating a cue, although painful, is by no means comparable with crowning and pushing an 8 pounder out of your vagina (even an imaginary one). So don’t treat cues like your children. Throw them out the window, leave them on neighbours’ doorsteps, chuck them in a pond wrapped in a knotted bin liner. They don’t matter. Directors are always having to abandon the best scene they filmed to the cutting room floor in order to honour the rhythm and pace of the larger picture. The one thing you have over them is that you can use this stuff again, they can’t. So to use the terminology of the great Daniel Lanois, make them orphans and put them in little labelled orphan drawers. Mark “cool ambient cue” and file for another day. Today’s reject maybe next year’s prom queen, once you find that orphan princess a home.

Recuts

Death and Taxes, that’s an absolute for most human beings, add “Recuts” if you’re a media composer. If you don’t like them, find another job. If they play turmoil with your life, your art, your craft, you’re not approaching this right. Your ability to handle recuts and maintain the musical integrity of your score is what separates us from the snobby hoards of amazing composers who can’t cut it in the world of media. Your ability to convert a series of cuts, crops, extensions, and re-orders into a series of MIDI moves that doesn’t decimate your score is one of the greatest pleasures of our trade. This is where chess head comes onboard. But there are a few pitfalls you should avoid so you don’t go to the gun cabinet to stick the twelve bore under your chin.

- That’ll learn you, you let the inner ‘Horn’ out too early, you spent too long making your composition frame accurate and hit heavy to a sequence you knew they were going to change. What were you thinking, when they see this they’re not going to want to make any cuts because the music is so perfect…. Yerrrrright! More fool you. Work loosely to early cuts and let the director know it’s loose to picture. She / he won’t care, the editor will, which is why he won’t put your music in his next cut. But the chances of that are light anyway so don’t stress it.

- Avoid using the picture to elevate your score. Write music that connects emotionally with the characters not with the action. It doesn’t matter what they do with the cut if the spirit of a wonderful composition is trumping everything else.

- Use ‘hit tricks’: Hit cuts with double or flamming drums so the cut happens somewhere in the middle of the two hits… Use very high tempo pieces for action sequences, ie drum and bass… that way any 16th will catch a cut pretty much. “Interesting 16th push there, high five” composer looks to the camera and winks.

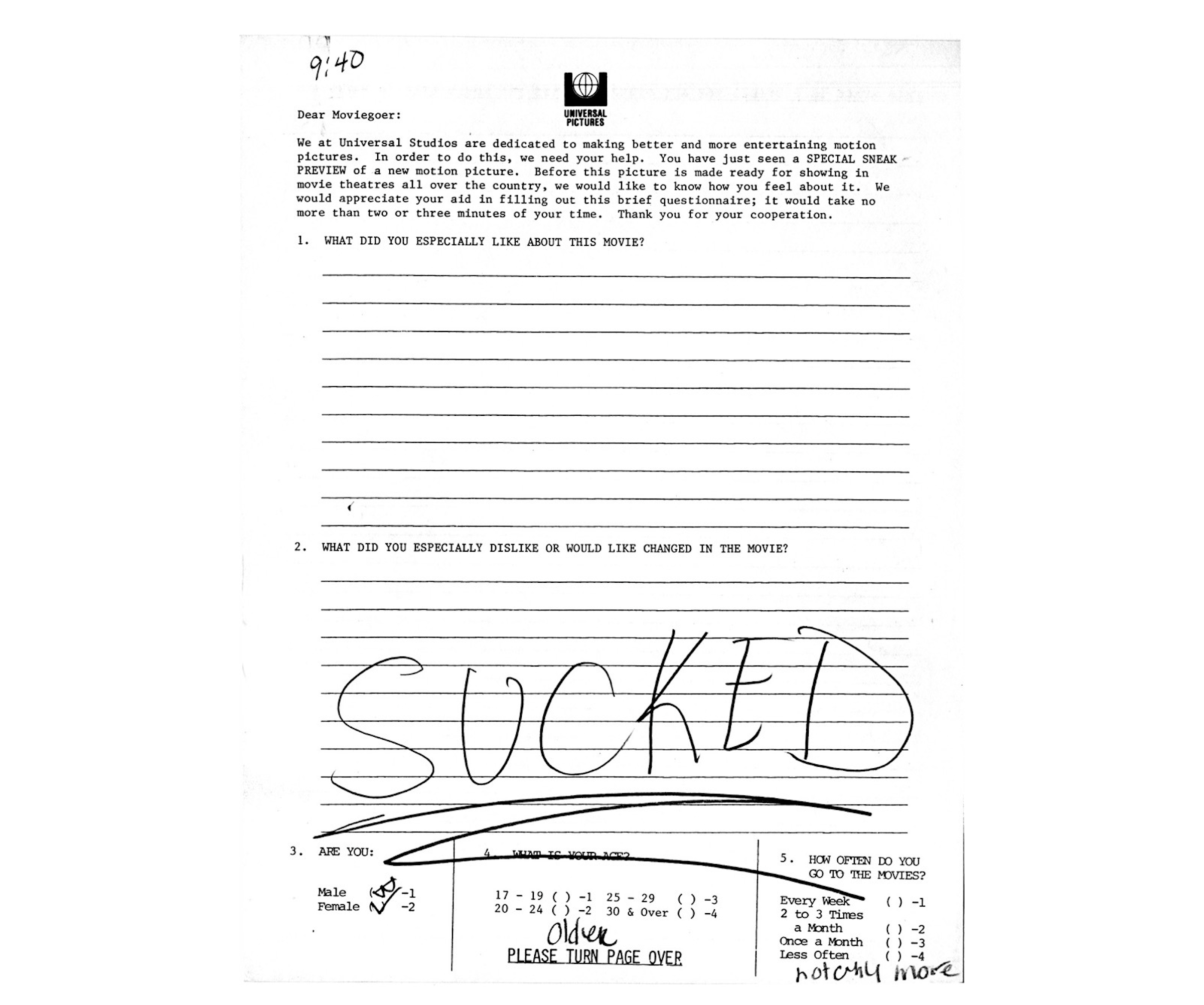

Test screenings

You know that dream where you reading some poetry at school assembly and you look down to realise you have forgotten to put anything on other than your shirt, and you’re stark bollock naked from the belt down.

Welcome to test screenings.

I heard one director describe attending the focus group after a test screening of his film as being “...as much fun as visiting the toilets in the Leicester Square 24-Hour McDonalds at 2am on a Saturday night”. Old Testament-style misery.

But test screenings have sunk many a fine composer too, and here’s why…

The film, into which the director has poured 4 years of his life, is finally shown to an invited audience of non-mates, and then everyone is asked a bunch of horribly leading questions (“Was the lead actor believable?”) by an independent market researcher with no attachment to the film, and a political commentator’s skill for needling out every last ounce of criticism.

The producers, director and occasionally composer sit at the back, mute, as members of the public dismissively reject their years of hard work as “not funny”, “too long” or worse.

When it’s all gone badly, here’s how the conversation plays out:

Market Researcher (upbeat, positive): So, what did you all like about the movie?

Focus Group: [SILENCE]

MR (recovering quickly): What about [famous lead actor] who played [important character in film]?

Focus Group: [SILENCE]

MR: Did you like the character?

Focus Group Member 1: Not really, he was a bit wooden.

Focus Group: [murmurs of agreement]

Director / Producer Internal Monologue (panicking): There’s not much we can do about [famous lead actor] being in the film. He’s in 75% of everything we shot.

Focus Group Member 2: Yeah, and it was all a bit confusing

MR: You said “confusing”. What specifically was confusing?

Focus Group Member 2: Well, nothing he said made any sense

Director / Producer Internal Monologue (increasing panic): Nothing?! There’s not much we can do about the script at this stage. We’ve shot the film now. [Famous lead actor] is already on Massive Apocalypse 2 and has grown a beard. We can’t even reshoot anything.

Focus Group Member 3 (chipping in helpfully with an unconnected remark): [Huge International Female Star] looked ugly with that weird make-up. I don’t even know how they could make [Huge International Female Star] look ugly.

Focus Group: [laughs in agreement]

Director / Producer Internal Monologue (increasing panic): Make-up?! Christ!

Focus Group Member 4: What was [up and coming TV heartthrob] even doing in the movie?

Focus Group Member 5: That in-and-out-of-focus thing every time we saw [1970s idol in last pre-retirement supporting role] made me dizzy. And was weird. And didn’t make sense...

Focus Group Member 1: I couldn’t tell if it was supposed to be sad or happy...

Focus Group Member 2: They’d never have worn those clothes back then...

Focus Group Member 3: …

Director / Producer Internal Monologue: Woah! Go back one. “Sad” and “happy” are emotions, right? You can manipulate those with music, right? There’s a light at the end of this dark tunnel!

MR (having been nudged forcefully by gesticulating director): Did you like the score?

Focus Group (collectively): Meh

MR: The music…?

Focus Group Member 1: I liked [hummable 80s hit]. Didn’t really notice any other music.

MR: So you hated the music?

Focus Group Member 2: I didn’t really notice the music either.

MR: So you thought the music was distracting and added to the sense of confusion?

Focus Group (as one): Well, it WAS confusing…

Director / Producer Internal Monologue (relieved): Yes! Thank God! It’s the music which is the problem and that’s something we can still fix. If we can just make it happier / sadder / get a different composer we’ll be OK...

And THAT is why composers are often the first to go after a test screening which has gone badly.

Part three is here

Next time, we’ll try and get you across the finish tape with our advice on gently encouraging your collaborators to sign off on cues so you can get prepared for the most challenging, the most nerve wracking, but also the greatest part of being a film composer… PRODUCTION! But we’ll also start the next chapter with the more sobering section header “getting fired”, it’s OK, you pass Jail, and get to start back at Go without collecting 200 bucks, but it is rarely the end of the world, or indeed your career.